Which headlines work best?

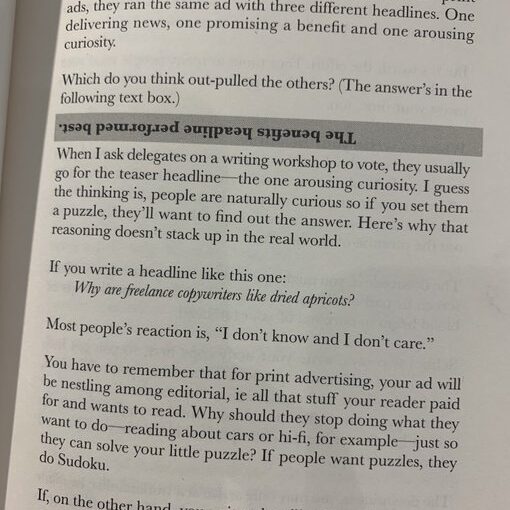

When a big US advertising agency tested headlines for print ads, they ran the same ad with three different headlines. One delivering news, one promising a benefit and one arousing curiosity, Which do you think out-pulled the others? (The answer’s in the following text box.)

The benefits headline performed best.

When I ask delegates on a writing workshop to vote, they usually go for the teaser headline—the one arousing curiosity. I guess the thinking is, people are naturally curious so if you set them a puzzle, they’ll want to find out the answer. Here’s why that reasoning doesn’t stack up in the real world.

If you write a headline like this one:

Why are freelance copywriters like dried apricots?

Most people’s reaction is, “I don’t know and I don’t care.”

You have to remember that for print advertising, your ad will be nestling among editorial, ie all that stuff your reader paid for and wants to mad. Why should they stop doing what they want to do—reading about cars or hi-fi, for example–just so they can solve your little puzzle? If people want puzzles, they do Sudoku.

If, on the other hand, you write a headline like this one:

How this freelance copywriter can help you double your sales

I think they’ll want to know more.

Excerpt from: Write to Sell: The Ultimate Guide to Great Copywriting by Andy Maslen